Chances are you have never heard of George Bliss. The superstar Chicago Tribune reporter won a 1962 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting and was associated with two others. But in my time at the Trib, while on a research project to commemorate the paper’s immortals, I learned he’d been practically expunged from its history. Here’s why:

In 1977, he took a leave of absence for bipolar condition; a year later, he shot his wife and then himself.

It was another self-inflicted, tragic ending with a firearm; Washington Post publisher and co-owner Phil Graham, also bipolar, died the same way in 1963. And yet, such tragedies are compounded by silence and institutional shame. In that Candy Land known as The Enlightened Workplace, we swear that we know better today. And in some ways we do. Due to the unprecedented stresses and isolation of COVID-19, we definitely converse more openly about mental illness on the job. We also write fearless, well-researched articles about it. All that is good, very good.

But as May is Mental Health Awareness month, my hope is to fire some well-placed shots across the bow. For starters, I suspect many of the conversations are the result of politically correct DEI initiatives. Translation in the C-suite: “We don’t want to face legal action or, gawd ferbid, bad PR. Let’s get out in front of this. By golly, let’s look like we’re doing something.”

The reality is much closer to this:

Mental illness is the last frontier of condoned, passively permitted and even encouraged prejudice in the newsroom — and the workplace in general. I know because I’ve experienced it, recently in fact. (More in a bit.)

Mental illness in the workplace is misunderstood

Cancer is a terrible disease; my father suffered from prostate cancer. It deserves sensitivity from bosses and gets it 110 percent. No one would ever marginalize an employee who’s revealed that they’re fighting it. In fact, people (as they should) line up at the person’s front door with casseroles. But such compassion does not translate for those with depression, acute anxiety, bipolar or other such struggles. An acquaintance, in the midst of a mental illness bout, dished a quip redolent of dark humor: “Who forgot to bring the casserole?”

And that’s the irony: Mental illness is a disease, too. Yet people who should know better assume it is a character defect, a descent into utter madness — or even worse, as workplace parlance goes, a lack of initiative. Sounds so official, doesn’t it? Yet this is how ignorance and prejudice perpetuate. We can and do hide behind the mandates of the job as a safe excuse not to take proper actions: to start by saying, “I hear you. I’ll keep this confidential. How can I help?”

We need that more than ever. According to statistics cited by Johns Hopkins University:

An estimated 26% of Americans ages 18 and older — about 1 in 4 adults — suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year. Many people suffer from more than one mental disorder at a given time.

John Crowley, a freelance editor and media consultant, has studied the phenomenon specifically in the news profession. Here’s what Worklife contributor Jessica Davies reported in December 2020.

In April, Crowley surveyed 130 journalists from a range of media companies globally and published the results in a report in November. In the report, 64% of respondents said they hadn’t had any positive work experiences during lockdowns, and 77% said that they had experienced work-related stress. A total 59% said they had experienced moments of feeling depressed or anxious.

Crowley has been brave enough to confess that he, too, has suffered from newsroom burnout. Now it’s my turn. Several times in my career, I’ve submitted to the symptoms of bipolar condition (not “disorder,” as I believe the term just reinforces the screw-loose stereotype). I thought I deserved credit for the moxie to press on. Instead, I saw a whole lot of nervous stares and arms-length treatment — along with colleagues, I should note, who stepped forward with care and concern. The trouble is that these good people acted on their own and not as the result of overall awareness driving a newsroom value.

My story, the good and the evil

I will always be grateful to a past employer who opened up a safe discussion about mental health issues at work. The outpouring of stories, all with names attached to them, described anxiety, perpetual lack of motivation, blue-ness, thoughts out of control — even suicidal urges. Everyone felt safe, and thanks to that company’s DEI committee, that safety was never called into question. I felt floored. Not alone. Unafraid.

And yet in more than a few stops on my career journey, a diametrically opposite attitude has prevailed. At one media outlet, my attempts to reveal my difficulties only created an impression that I was unhinged. I learned — as have many others I know — simply to keep my trap shut.

Most recently, I was in a full-time, media-related position at a prominent employer where my decision to share simply fell on deaf ears. The trouble began days after I signed on. A higher-up in the department (with an uncanny resemblance to a bespectacled Cruella De Vil) soon revealed herself a narcissist and a bully without boundaries. She would email on weekends and long after work hours. She micromanaged people’s tasks and bombarded email boxes while on vacation. Soon she put me on the defensive for not meeting her standards — impossible, since they only existed in her mind.

I took at least one mental health day to avoid being in her line of fire. I dipped into anxiety as she began to scrutinize my every move — and even question my interviewing technique, Pulitzer Prize finalist status be damned. When I received workplace kudos and praise she simply re-ran it through her own lens. In her not-so-funhouse mirror view, I was found wanting.

On one day, a work assignment got cancelled and I took a few hours off to air my head; a mental health “half day,” if you will. Soon my immediate supervisor (who was her subordinate) knocked on my Zoom room door to ask what I was up to. Nervously, I confided that I was having mental health symptoms, that I was teetering.

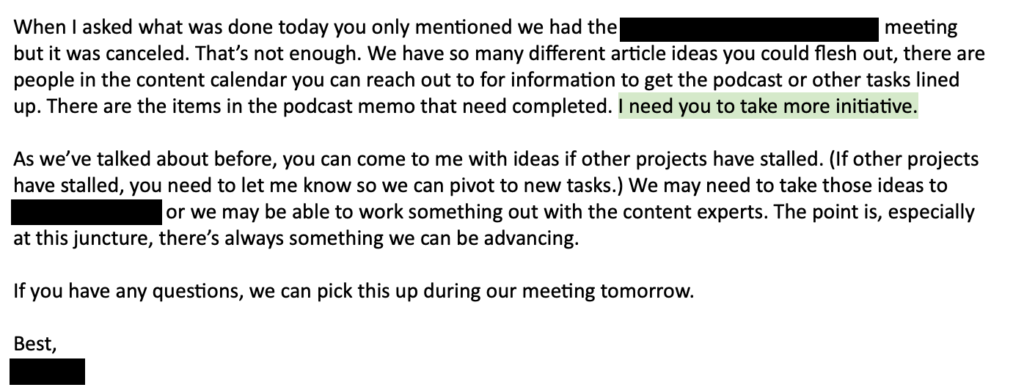

But I’d been down this road before with middling middle managers. Experience taught me to take notes during meetings, so I was prepared. I documented the conversation in full — what I told him about feeling too scrutinized, the mental health symptoms I had, how hard it was to come forward … and how he reacted. “P Hat” (not his real name) didn’t say much. He did want to know why I hadn’t mentioned it earlier. But beyond that, nothing — until I received an email nearly three hours after work’s end, not long before my bedtime. It said, insofar as my recent work performance, “That’s not enough. … I need you to take more initiative.”

Why my work life is so much better now

I can’t tell you how much hurt I felt — and then shame when P Hat fired me few days later. When I asked for a reason, he gave the blank stare of a drone in a Stanley Milgram experiment and said, “You don’t like being micromanaged.” But it didn’t take long for my embarrassment to turn into rage. I had confided one of the most personal parts of life and work to this guy, expecting he would help. Or at least sympathize. But … he ignored me? Then chastised me? Was he taking his directives from the bully, who herself left for greener pastures within hours of my dismissal? It seems likely. The way-after-hours work email in her style was a clue. But I’ll never know.

I do know this: Super-friendly colleagues at that workplace from my freelance days, whom I encouraged through tough spots, and new friends alike ghosted me. I emailed, I reached out. Again. And … nothing. (Maybe they think I’m crazy, eh?) Though no court of law would ever consider a case, the damage has been done and can likely never be undone. Personal losses sustained and yet, case dismissed.

In leaving names and workplaces out, I seek only to tell my story. Besides, the people responsible for the events are safe, insulated by look-the-other-way big bosses and elite corporate lawyers. Speaking of which, I consulted a lawyer who said he felt reasonably confident he could get me my job back. I decided a return ticket to hell was not worth pursuing.

Instead, I’ve chosen a high road and a smarter one, I think. As a full-time freelancer, I get to decide whom I work with. Bullies and punks get shown the door. Those who lack the compassion to walk beside colleagues forthright about their mental health struggles will have to seek services elsewhere.

My name is Louis R. Carlozo, and I was some years ago diagnosed with bipolar II condition. On an overwhelming number of days, I do my job exceedingly well and sometimes my manic cycles make me indefatigable in ways no twentysomething go-getter could hope to match. But when I experience undue pressure and intimidation in the workplace, it hits me much harder than many others. If I tell the truth about my troubles, it can bite me in the ass. And if I stay silent, it can make my slips in performance a mystery to those around me. “What’s he hiding?” Well, wouldn’t you like to know?

But enough hiding — something I don’t have to do at Qwoted or its parent company Vested, thank God. I’m also thankful for brave media colleagues like National Book Award winner Andrew Solomon and Atlantic editor Scott Stossel, who have written about their mental health issues with bravery and often a biting wit. They’ve inspired me — in no small part because they’ve moved to places in their careers where a clueless manager like P Hat can’t topple them in their honesty.

If you get the vagaries of workplace mental health, I salute you with utmost warmth and thanks. And if you don’t that’s OK — but please don’t judge or act like an ignorant asswipe as so many others do. The person who suffers in silence may be sitting over in the next cubicle. Or at the table across you in the coffeeshop. Or at dinner. It could be your spouse. Your kid.

Maybe you.

If so, you’re far from alone. If you reach out, many others will reach back. Count me as one of them. There is hope. Progress is slow. But we are making progress, right? Journalism at its core is about truth and light doing its best to cleanse the dark places. It’s time to stop cowering there: to come out and sing who we are, broken notes and all. It’s OK, as they say, not to be OK.

Lou Carlozo is Qwoted’s Editor In Chief. He was diagnosed with bipolar II condition in 2001 and has suffered several bouts of depression and generalized anxiety. All opinions expressed are his own. Email lou@qwoted.com or connect on LinkedIn.