Inside the Chicago Reader’s bizarre battle to overcome a stubborn co-owner and survive

It’s a fairly bizarre thing to me that on landing fresh at the Chicago Tribune in 1993, more wet behind the ears than a cub reporter doused in a waterfall, senior staffers recommended that I immediately start reading another hometown paper to stay on to of the city’s arts, culture, entertainment and long-form journalism forays.

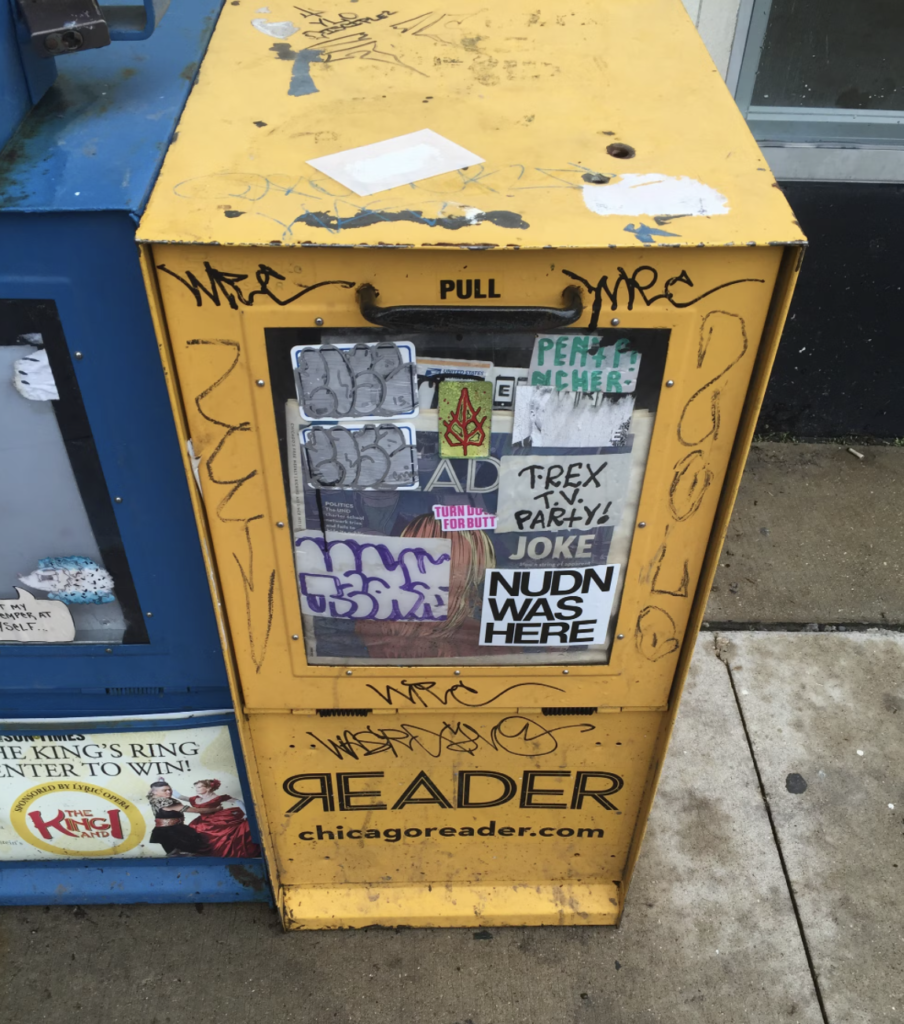

But it wasn’t long before I became hooked on the Chicago Reader, the free paper that hit local record stores, restaurants and newspaper boxes every Thursday. You had to move fast; if you didn’t get your Reader by mid-afternoon, you might be out of luck. The alt-weekly had been a local institution since 1971, when a group of Carleton College graduates launched it on a wing, a prayer and a lark. Their timing couldn’t have been better; newspaper advertising was about to explode for feisty metro weeklies.

Back in the pre-Internet days, the Reader was as thick as a phone book. But just as a Yellow Pages in every home is a long-ago memory, the Reader soon could be, as it fights to stay alive — and plow past the iron will of a co-owner whose wounded pride stands in the way of the paper’s transition to a non-profit.

From a bad column to bad blood

Last week, Reader staffers gathered in front of the home of Len Goodman—a criminal defense attorney and center of controversy ever since he wrote an opinion piece in November about why he was reluctant to vaccinate his 6-year-old daughter against COVID-19.

Goodman’s column was riddled with factual miscues. The Reader suffered a good amount of backlash and might well have pulled the piece or revised it significantly. That was at least the plan. Still, there remained one nagging detail: Goodman bought the struggling weekly for $1 from the Chicago Sun-Times in 2018, along with prominent real estate developer Elzie Higginbottom. And he wasn’t about to let his published piece of half-cocked doggerel submit to the same rigorous fact-checking that every other journalist accepts as de rigueur.

Sayeth Goodman: “Editorial control is before you publish, not after you publish something and there’s a public outcry to take it down.”

Wow. I didn’t realize that. Thanks, Len.

And so, instead of letting the Reader go the non-profit route that will guarantee its survival—something the Sun-Times itself pulled off just a few months ago—Goodman has chosen to starve it to the point of death. The Reader has been stuck in limbo since December. In weeks, perhaps days, it will run out of money entirely.

Pride and incompetence

Assumedly, this could all be cleared up if editor Tracy Baim would just, oh, cave in and grant Goodman the investigation he demands into what happened to his precious little column. (Note to the defense attorney: There’s this little thing called accuracy. I’m sure you’ve heard about it.)

The tantrum has even baffled the Reader’s other owner. “We’re supposed to do this, and Len is stuck on the fact that there was some question about his article,” Higginbottom, 80, told the Chicago Tribune. “I was willing to go forward.”

This is where cluelessness enters the picture. A Reader board member Higginbottom himself appointed–Chicago Crusader publisher Dorothy Leavell–decided that Goodman had a point after all. On Dec. 17, she voted with another member of the three-member for-profit board to stall the scheduled transition, just two weeks way, until Goodman’s piece was “further investigated and resolved.”

Here’s what she told the Tribune in justifying her vote: “I didn’t agree with how they had treated the article that Mr. Goodman had written.” With that spirited defense for shoddy opinion disguised as press freedom, I rank Leavall right up there with giants of journalism. Really, I do. As in: Giant. Freaking. Idiot. It’s truly something to stand on the shoulders of mental midgets and sympathize with their whining, even if it means letting a storied local institution go down in flames.

If I form a board, I damn well want Leavall on it. I’m assuming it will have something to do with Defending the Criminally Immature.

You can’t trod on a track record

As if this isn’t enough, Goodman is also insisting on more representation on the successor board of the non-profit, the Reader Institute for Community Journalism (which Baim co-created in December 2019). But why? Control, of course, is key. Trouble is, I think self-control (that is, the lack of it) is getting in the way here.

If Goodman gets his way and destroys the Reader in the process, it will be a damn shame for all us Chicagoans who grew up on it, found undiscovered bands through it, relished the investigative pieces of police misconduct and corruption that ran in it.

For countless numbers of us, the Reader served as nothing less than a print pre-Twitter. People ran mini-personals–constantly–in last-ditch attempts to reach the hotties they locked eyes with on the El for a brief moment. And there were the ads: thousands of them. If Noah were in search of an ark in the ’90s, he’d have found it in the Reader. You could advertise anything from a fetish-based relationship opportunity to metal-shop gear that fell off a truck, or toys meant to con a budding percussionist. I still remember one infamous classified: “DRUM KIT, STILL NEW IN BOX, $300.” All the musicians in town knew about it. The seller’s “new” drum kit, a cheap piece of crap, apparently bred like a bunny as the ad ran continuously for years.

It’s hard to believe that this paper–a long-and-slow casualty of the online movement, dwindling ad revenue and the pandemic–sold in 2007 for a seven-figure sum. One of the feisty college kids who started it was approaching retirement age; his creation was struggling even then as the tides of local journalism changed, Craigslist poached classifieds and an internal lawsuit raged.

In the face of insanity, a crazy idea

But perhaps all hope is not lost if the Reader can somehow, someway follow an unconventional tack. Though on a much smaller scale, there is precedent. In the Vietnam War era, student journalists at Loyola University Chicago began to decry the conflict as senseless and deadly. Assuming that press freedom was a classroom exercise only, school officials shut the newspaper down. After laying low for just a bit, the weekly reformed itself–and retains the name Loyola Phoenix to this day. I spent 10 proud years there as the faculty advisor, and the story as students related it to me remains an inspiration.

I assume that if Baim and her allies have the pluck and the creativity, they could do something similar: reform the Reader under a different guise not beholden to Goodman one iota. Sure, they would lose the archives of the paper, its name and a whole lot more. But it would survive and rise in phoenix-like style. And should Goodman tire of holding the paper hostage–hey, he wouldn’t have anyone to censor an error-riddled obituary–maybe its assets could be obtained again in time, the brand rebooted.

It’s the kind of nutty scheme you’d expect to read, once upon a time, in the Reader.

Lou Carlozo is Qwoted’s Editor in Chief. All views expressed are riddled with lapses in judgement that he will fight to the death. Email lou@qwoted.com or connect on LinkedIn.

POPULAR POSTS

LATEST ARTICLES

CATEGORIES